Living The Truest Reality

Last night in our Young Adult Bible Study Group we discussed the "Parable of the Talents." You may know the story.

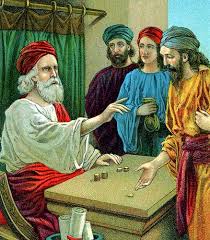

Last night in our Young Adult Bible Study Group we discussed the "Parable of the Talents." You may know the story.A very wealthy man goes on a trip but in his absence he decides to entrust some of his wealth to three of his servants. According to their ability, he divides the money among them. To one servant he gives 5 bags of gold (or "Talents"--the highest ancient Roman currency), to the next he gives 3, and to the last one he gives just 1 (still a significant amount of funding). Now, all three servants knew that the master was really into his money, they knew that if they gave back less than what they were given then they'd be in trouble. The two of them, being quite prudent and yet risky, decided to put the money to work and get some dividends. But the last servant, the one with the least cash, sorta freaked out. fearful of his master, knowing that his master would return shortly, he decides to protect the money and simply bury it until the master returned. When the master returned he rewarded the first two servants and essentially killed the third one saying "throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth."

Now we often read this passage all by itself, but it's important to be aware of its context. The story is found sandwiched between two other stories... one about ten virgins and another about some sheep and goats (Jesus really liked to the explore a wide range of illustrative elements). Now if we read the story of the "Talents" all by itself we might easily come to the conclusion that God is not too nice. We'll almost immediately presume that the Master in the story is a direct representation of God himself, that the character is offering clues as to what kind of God Jesus has been talking about. We might picture a God who is ready to throw us in the fires of hell if we don't make dividends off of the stuff he gives us. We might then choose to live lives of fear (ironically, just like the third unfortunate servant) and we might be driven by that fear to do all sorts of things to avoid punishment. The gospel--which is supposed to mean "good news"--might start to look a lot like bad news.

But perhaps the Ten Virgins, the sheep, and the goats might be able to help us get a fuller understanding of what's going on in the story. I encourage you to go and read the two stories, as I am sure my quick synopses will do no service to them here.

The ten virgins were waiting for the bridegroom to show up. Apparently, they really wanted to get into a wedding banquet but they had to line up outside and wait for the bridegroom (kinda like waiting outside BestBuy on Black Friday)--the bridegroom was their ticket inside. Five of the virgins brought enough oil for their lamps, five didn't. The five who didn't missed out on the party because they had to run back and get some more oil for their lamps. The story ends with this cryptic warning, "keep watch, because you do not know the day or the hour."

In the story of the sheep and goats, Jesus is describing the return of the "Son of Man" (no doubt referring to himself). When he comes back (from wherever it is he is going) he separates all the nations like sheep from goats. Now the way he does this dividing is not based on how much money they earned, it's not based on whether or not they were prepared for the wait, it's based on how well they treated the "least of these"--those who are unwanted and needy in their society. The thesis, if you will, of the story is "whatever you did for one of the least of these... you did for me." There's no question in this story as to what's most important to the king--not money, no dividends, but people (and lowly ones at that).

so what happens when we put the three stories together? The first story tells us to be ready, the second story tells us not to live out of fear of our Master, and the third story tells us what's most important to our "master." In each story there is anticipation for the arrival of someone... a master, a king, a bridegroom. The question is what's the proper practical response to such anticipation. Should we live in haste, assuming that it's gonna happen soon enough that we don't really have to worry about sustaining things ("forget about the next generations, Jesus is comin' soon!")? Should we live in fear that if we don't do things just right then we'll displease our angry God, which will actually paralyze us from doing anything at all and will actually blind us from really understanding what's important to our master--the need of others and the "least of these"?

Our actions, our choices, indeed what's happening in our hearts is a reflection of God himself. But is it an accurate reflection or a distortion? Are we living lives of perpetual readiness? Are we, like the two good servants, reflecting the reality that there is plenty more where this came from? Are we doing with our time, our money, our gifts, and our circumstances what God "from whom all blessings flow" would do with them? Are we reflecting, with our lives, the truth about what's most important to God? Indeed, are we calling that which we anticipate--that future reality--into the present? Or are we hastily waiting as though we can have no part in it today? Are we just waiting for God to come or can we actually see him and find him in all the hidden places around us?

When I put these three stories together, I hear a call to not just live for the future but to live-out the future and to make it the present. I don't want to wait so as to be disappointed when the wait turns out to be too long. I don't want to hide and protect myself in "safety" out of fear and haste. I want to reflect the image of my God now.

If our anticipation is all about the future and if we're afraid to take the risk of truly living today--twirled in fear and haste (like the virgins and the servants)--then we're going to end up paralyzed and blind. We'll be paralyzed from living in God's kingdom here and now, paralyzed from making that kingdom a reality for those who are in such need of it in their lives today, and blind from seeing God in the unexpected people and places all around us here and now!

The Parable of the "Talents" is a call to take the risk of living according to the truest reality, out of faith and knowledge of who God is and where all we have actually comes from. And it's a call to start living it today.